The Armenian Weekly Magazine

April 2015: A Century of Resistance

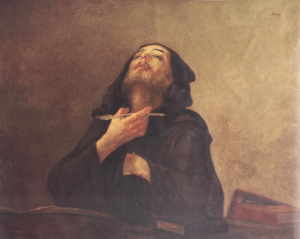

The voice of a sighing heart, its sobs and mournful cries,

I offer up to you, O seer of Secrets,

Placing the fruits of my wavering mind

As a savory sacrifice on the fire of my grieving soul

To be delivered to you in the censer of my will.

—St. Grigor Narekatsi

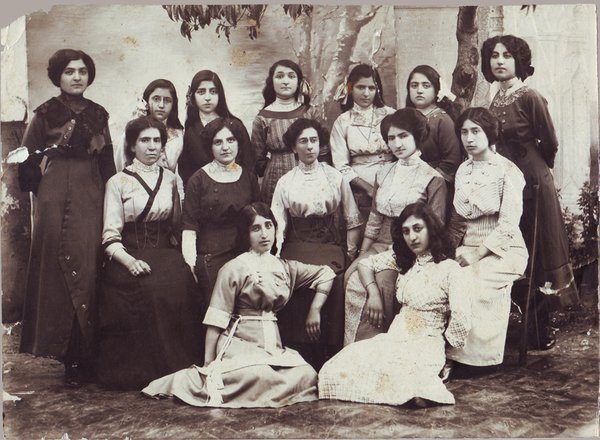

As I read and look through various books and papers on the Armenian Genocide, I think of the genocide survivors I met and got to know years ago in the Chicago Armenian community. The community elders would say with reverence, “See that lady over there, she is one of the Survivors… That man there, he is one of the Survivors…” There were several of them, and they were always working—serving our Armenian community—in the church, church hall, kitchen, school, and on picnic grounds. Occasionally, one of them would begin singing in the church hall’s kitchen. Within no time, others would join in, and as one voice they would sing, as they diligently prepared Armenian dishes for a community function, as they stayed behind after an event to clean and tidy up.

Though the aromas that wafted from the kitchen or picnic grounds were delightful and inviting, the unwavering enthusiasm and devotion these particular individuals felt for their people and community were awe-inspiring and unforgettable, for they had come from a place where they had suffered and survived unspeakable horrors simply because of who they were—Armenians and Christians. As a result, they had lost everything—family and childhood, home and hearth, hopes and dreams, even their identity at times. Despite the carnage, destruction, and immeasurable loss that had befallen them, they were able not only to overcome their sufferings and go on with their lives in far-away lands, learning new languages, customs, and traditions, but also to give of themselves and enrich the lives of others, especially their Diasporan Armenian communities.

Years ago, during interviews I had conducted with some of these survivors in their homes, I noticed that though each had come from different regions in their homeland, and from different socio-economic standings, when they spoke of the horrors they had suffered they all described similar atrocities. And, when they spoke, each had the same heart-wrenching sorrow in his or her eyes.

I began the interviews first with a male survivor of the 1894-96 Hamidian Massacres. The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 had granted the Armenians certain rights. At last, the Armenians thought, they could allow themselves to look forward to a decent life, free of fear, brutality, and massacres. That sentiment, however, was short lived. During the late 1800’s, sporadic massacres of Armenians were carried out, beginning in Van. Upon learning of the atrocities that had begun soon after the signing of the constitution, Patriarch Khrimian Hayrik “charged that the government was guilty of perpetrating the crime and inciting violence.” In a pamphlet called “Haikouyzh,” the patriarch wrote, “They fell upon and covered Armenian villages and farms like locust and worm, devoured and withered all vegetation and turned fertile villages and towns into barren wastelands” (from The Pillars of the Armenian Church by Dickran H. Boyajian).

Clik here to view.

Painting of Grigor Narekatsi by artist Arshag Fetvadjian

Mrs. Carlier, the wife of the French Consul in Sepastia, an eyewitness to the massacres and deportations that took place in 1895-96, wrote: “They killed everyone in the market place. Not a single Armenian remains. … Right at this moment they are killing with bayonets. … Since the mob was not armed with weapons, they had grabbed whatever they had found, axes, clubs, stones and shovels. They crushed the heads of the victims… Everywhere there is blood; wherever you step, you step on human brains and scalps. … I saw dogs dragging human body parts in their mouths… blood dripping from their mouths. … The majority of the victims were men. A large number of women and girls were put up for auction by the criminal Turks. … The women and girls were raped with extreme barbarism…” (from Village World [Kiughashkharh] by Vahan Hambartsumian).

The following are brief excerpts from four of the interviews.

The survivor of the 1896 massacres described the day the Turks came in these words: “My family was from Sepastia,

and we Armenians always lived in fear. My father was a priest. I was five years old and playing with my friends

outside, when suddenly we heard a great deal of noise down the street. There was much yelling and screaming. A crowd was coming and they were carrying daggers, pieces of wood, anything with which to kill a person. People were running, and there was blood everywhere. The Turks were killing anyone they could get their hands on. … I ran and hid in a hole in the ground, which was filled with ashes, for about two or three days. When I came out of the hole, I was very thirsty and hungry… Because of what I had witnessed I developed a severe stutter. Nearly 90 now, I still stutter.”

In 1915, four years after immigrating to the United States and making Chicago his home, this survivor, upon learning of the plight of the Armenians in his homeland, left for the Caucasus to join other “gamavors” (volunteers) in fighting the Turks.

A female survivor of the genocide recalled, “I was seven years old when the Turks came to our village in Sepastia. They killed so many Armenians, including my parents, sisters, and brothers—my whole family. I do not know how I survived, but I remember seeing blood everywhere and so many people on the ground. I was walking and walking, calling for my mother, when two gendarmes saw me and hurt me… I was full of blood. Someone carried me to a hospital, where the doctor, who knew my family, wept when he saw me… Later, I was taken to a Turkish couple and I stayed with them.

One day, when I was outside, some Turkish boys and girls screamed and shouted ‘gavour’ [nonbeliever or infidel] at me. As they repeated that word, again and again, they threw rocks at me… You can still see the scar on my face. … After staying with the Turkish couple for a while, I was taken to an orphanage in Marsovan, then to one in Greece, and later, when we orphans were older, some of us were sent to France. So many lost their minds because of what the Turks had done… Whenever I thought of my family, my home… I could not stop crying. … We had such fun playing together, my sisters, brothers, and I. We had a nice home, and a beautiful church before the Turks did the things they did.”

A female survivor from Dikranagerd told of her ordeal in 1915 as she looked down at her hands resting in her lap. “I was fortunate to only have my fingers cut off of one hand. Some had hands and other body parts cut off, but mostly they were murdered.”

A male survivor from Urfa recalled, “I was 10 years old in 1915 when it happened. I was outside walking down the street, when I saw some Turks killing an Armenian. They were striking him with canes, knives, swords, shovels… I was terrified and found a place to hide. When it was safe I ran back home where I found my uncle dead. They had slaughtered him like a lamb on the steps of our house. His head was down and his feet were up; there was blood everywhere. My father and other Armenian men were taken away. We never saw them again. My older brother, who was 19, had his head smashed. Some of my other relatives were killed. My mother suddenly could not speak and died three days after they took away my father and killed my brother. … The Turks filled our church with Armenians, and they burned them, even the children. They burned them all! I saw it. I saw a lot. … A Turkish family, the one that had earlier taken away my sister to be a wife, took my little brother and me to their house. There, we were made Turks and given Turkish names. I was called Hasan… Eventually, when we got older, we left and once again used our Armenian names. … It was God’s miracle that the two of us survived. At times, after all these many years, I still see my dead mother and my brother with his smashed head, and all the others who had been killed, before my eyes.”

Though the survivors I spoke with, and got to know many years ago, have all passed away, their stories—the story of a nation nearly annihilated by another—can still be “heard” via countless pages of printed material. For example, in the Oct. 7, 1896 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, an article titled, “Chicago’s Work for the Armenians.” described the efforts of the “Chicago Armenian committee” in collecting $13,000 for the “International committee” in Constantinople to assist destitute Armenians who had survived the 1894-96 massacres. Also mentioned were the efforts of the Salvation Army in preparing to assist these refugees in establishing homes in America once they arrived.

As the sporadic massacres of the later 1800’s continued into the early 1900’s, behind the backdrop of World War I, methodically and with great acumen, the Turkish government, in 1915, began its ultimate endeavor in the total annihilation of the Armenian people and culture. The following are more examples published in the Chicago Daily Tribune, reporting on the plight of the Armenians.

In the May 18, 1915 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, a caption on page 4 announced the slaughter of 6,000 Armenians by the Turks, and that aid to Armenia was needed.

In the Jan. 26 1916 issue of the same paper, an article titled, “Chicago Asked to Open Purses for Armenians,” described the dire plight of the Armenians, growing more critical every day because of the countless massacres, as well as the starvation, disease, exposure to the elements, and homelessness they were suffering.

In the Feb. 1, 1919 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, an article titled, “5th Liberty Loan Workers Told of Armenians’ Woe,” outlined a speech given by the former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Abram L. Elkus at the Morrison Hotel in Chicago. The ambassador began his speech by telling the audience that he had no real idea what hunger and poverty were until he saw the devastation of Turkey’s Armenians. He told of the hunger and poverty, the despair and death, and the 400,000 Armenian orphans that crowded into available buildings. He described how he and a friend had counted on the roads of Asia Minor the skeletons of hundreds of Armenians who had been “butchered by Turks.”

In the March 17, 1920 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, an article titled, “Evanston Girl One of Three Helping 67,000 Armenians,” described the work of Miss Alice K. Clark of Evanston, Ill., the daughter of the manager of the American Stove Company, and 2 other members of the American Relief Committee in Hadjin, Turkey, caring for 67,000 Armenian refugees.

After all these years—One Hundred—Turkey continues to deny any wrongdoing, stating that the Armenian Genocide never took place and that the issue of the Armenians “should be left to historians.” Yet, as one reads the numerous eyewitness accounts, reports, newspaper articles, and books, one wonders, How can a crime of such magnitude—a government’s systematic annihilation of nearly an entire race—be denied, and for so long? The numerous accounts, reports, and documents do not lie. The bones scattered across the land, the crumbling age-old churches and edifices do not lie.

In New York, the Alliance Weekly: A Journal of Christian Life and Missions published several articles, including eyewitness accounts, of the atrocities against the Armenians from 1909-19. The following are examples.

On Oct. 2, 1915, the Alliance Weekly published a piece titled, “Armenian Atrocities,” describing the condition of the Armenians in Turkey: “An appalling condition prevails in Armenia. A representative committee of Americans have secured and sifted reports from all parts of Turkey. A preliminary statement has been given to the press and a detailed survey will follow in a few days. Atrocities unparalleled in modern history will be revealed. Armenia is being depopulated of its Christian population whether Gregorian or Protestant. At least half a million have perished in massacres or of hunger in the wastes to which they are driven. The missionaries of the American Board at Bitlis, Van, and Diyarbakir have been driven out. …”

On Oct. 23, 1915, the Alliance Weekly published the following: “The Christian world is again shocked by the new story of Armenian atrocities. There, horrid cruelties are on a scale surpassing even the frightful wrongs of other years, which justified the title Mr. Gladstone gave to the Turkish ruler, ‘Abdul, the Assassin.’ The present policy of the Turkish authorities, with the tacit support, it is feared, of their German allies, is the utter extermination of this sturdy and superior race… the entire destruction of the race.”

In the Oct. 30, 1915 issue of the same publication, a returning missionary from Turkey, Dr. McNaughton, reported, “…The missionary work in Asia Minor, under the American Board, has been almost entirely wiped out. … Before the war there were 148 stations, 309 missionaries, 158 organized churches, 1,310 native helpers, 26,000 scholars in 450 schools and colleges, and 60,000 in attendance upon the missions. Today these flocks are scattered, and more than 1,000,000 Armenian Christians appear to have perished. … Is it the last drop in the full cup of Turkish crime?”

Clik here to view.

Painting of Gomidas, ‘Vercheen Geesher – Debee Aksor’ (‘Final Night – Toward Exile’)

In the Dec. 30, 1916 issue, an article titled, “Famine Horrors in the World War,” by A. E. Thompson describes the Armenian atrocities: “It has not been a conquered province that has suffered, but a subject nation, over which the Turks have ruled for centuries. Abdul Hamid shocked civilization by the massacres of a few thousand Armenians… He probably never conceived such horrors as the Young Turks, who dethroned him, have perpetrated. The report published by the Relief Committee states that out of a total Armenian population of 2,000,000 no less that 850,000 have died in massacres or of disease, exhaustion, and starvation… The report of the Relief Committee reads: ‘Men were led away in groups outside their villages and killed with clubs and axes. The Consul of one of the European nations reported that on one occasion 10,000 Armenians were taken out in boats, batteries of artillery trained upon them, and the entire company killed. Girls and women were reserved for an indescribable fate in terrible marches; in harems, in the houses of officials, or in tents of the wild tribes. Villages and towns by the hundreds were wrecked. The whole Armenian population of large sections deported. Of 450 in one village only one woman lives… Read the most graphic pictures in prophecy of horrors and outrages and you have a mild picture of what has occurred…”

In the Jan. 13, 1917 issue of the Alliance Weekly, an article titled, “The Turkey of Tomorrow,” by an author who signed the piece as “A Missionary Resident For Thirty Years In Turkey,” asks the questions, “What, then about the future? How about the wreck of work for Armenians after the holocaust that has destroyed more than half a million of them, deported and impoverished more than half a million more, forced another quarter million to flee the country? Can the churches ever be revived or the schools reopened? …

When many thousands have been faithful unto death, preferring a martyr’s crown to a Moslem life, the people all see that faith and life are the essentials, rather than creeds and ceremonies. The ancient Armenian Church will come forth from this ordeal ‘tried as by the fire.’”

In the Oct. 6, 1917 issue, an article titled, “The Crimes of Turkey,” begins: “An important conference of the friends of the great movement for Armenian and Syrian relief was held in New York City during Tuesday and Wednesday, September 11th and 12th, at which there was a representative attendance from the various churches, charitable and missionary boards and societies. … The Alliance Weekly was represented at this conference…” The article outlines the account of Dr. Frederick Coan, who was “an eyewitness of both tragedies.” He had stated, “the present massacre [1915] far exceeds in loss of life and desolation of land than that of the massacre of 1894-5.” He said he had stood by “a huge trench—the grave of two thousand Armenians, who had sought to defend themselves from the Turks until their ammunition gave out; who on asking at what terms they might surrender, and on being promised their safety (sworn to on the Koran) by the Turks, surrendered, and were immediately given spades and shovels and ordered to dig a trench. When this trench was completed, those 2,000 Armenians were driven into it at the point of bayonets, and there buried.” He told of standing by a pit, “the grave of 1,600 little children who had been gathered together, saturated with oil, and burned alive, while the fanatical Turks beat drums to drown their dying cries,” and “a bridge from which 1,600 young Armenian maidens had plunged to their deaths rather than live as slaves in Turkish harems.”

The piece included Dr. Coan’s appeal to America: “Christian America—help save those who still can be saved. Hundreds of thousands of refugees have fled to Russia. Here they can be reached, and the Russian government will not refuse their relief. Russia has never refused to help us in relief, even handing money to us to be distributed by us as we thought best.” The doctor’s presentation concluded with: “There are Mohammedans who do not approve of this massacre. Over and over again I have heard them say, ‘I wonder that God in heaven does not bring fire down and smite us for these deeds…’” (When the Russian and Armenian volunteer forces liberated Van in May 1915, working along with the American missionary aid workers were the Countess Aleksandra Lvovna Tolstaya, the youngest daughter of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, and her aid workers. See the correspondence of Grace H. Knapp [1895-1916], Mt. Holyoke College Archives & Special Collections.)

The article also includes the account of a 17-year-old boy who had been brought to the United States. At the time of the genocide, he was 15 and had escaped. He told of his harrowing experience: “On March 31st or April 1st, 1915, our city was suddenly surrounded by Turkish soldiers. Most of the prominent Armenians were imprisoned, among them my father, who was a professor in a college. They were asked to give up their guns, but as most of them were merchants, doctors, professors, etc., there were few guns among them. Then the officers beat them. The professor of history in our college was first beaten with a stick; his fingers were then burned, then his hair, and finally he was crucified. … The mothers began at once to cut off the hair of the girls, but they could not hide their beautiful eyes. … We were surrounded by other Turkish soldiers. They separated the men from the women and put the men in a great dungeon…in that prison 550 men were weeping. … The women and children were placed in another prison. … The next night 549 men were taken to the nearby mountains and killed one by one… From that group only one boy is living—myself. … Those 2,500 women and children. . . …they took away their clothing … drove them out to the deserts. Children were taken by the Turks…some of the women became Moslems and were spared. Others threw themselves into the river. … The prettiest children were selected by the Turks, especially the boys and girls from ten to twelve years. … Once they were free as birds, now the girls are imprisoned in Turkish harems, buried alive.” The boy’s account ended with: “A whole nation is being killed and deported by the Turks, and those remaining are dying of starvation…”

In the Oct. 25, 1962 issue of Milliyet (Istanbul), an article by Gunay Erinal (Assistant to the Agricultural Inspector) titled, “A Modern Turk on the Armenian Past,” describes what the Turkish people experienced years after the genocide. It begins: “There is a famine in Eastern Turkey. Last winter all the newspapers reported that animals were dying of hunger. … In the beginning of 1962 in Saimbeyli (Hagin), the villagers said: ‘In the days of the Armenians more people lived here; the grapes and their wine were very well known. At that time there was also a college, which disappeared with the Armenians. … In the days of the Armenians here…’ I had heard these words long ago, and I heard them very often recently. … ‘The villages of Hunu and Lorsun…’ Afsin and Elbistan as well… ‘When the Armenians were here there was a dam on the river by virtue of which we had no shortage of water. …’ In Hakkari also I heard Armenians mentioned. … ‘The Armenians, by planting terrace-vineyards on the steep mountain-side, produced grapes, and it was very successful. But it does not exist now. … Our people neglected the land. … In the Catak ‘kaza’ of Van there are thousands of pistachio nut trees, but they are not fertile. …’”

As the Armenian communities throughout the world prepare to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the 1915 Genocide, one cannot help but wonder, how has this small nation continued to thrive despite all it has suffered? The answer must lie in the Armenian people’s deep reverence for church, language, heritage, culture, and patriotism.

Author J. Alston Campbell, who was witness to the deplorable conditions and sufferings of the Armenians in Turkey, wrote, “The thousands of Armenians who laid down their lives at the time of the massacres did not die on behalf of a political propaganda, they laid down for the Gospel, as a testimony to the Moslem world of the power of a living Christ. Most of those martyrs, had they wished, might have saved themselves by holding up one little finger as a sign that they accepted Islam. But they chose death rather than deny His Name…” And, of the patriotism of the Armenians, he wrote, “A strong feature in their character, and this, together with a wonderful recuperative power which they possess, has often enabled them to rise phoenix-like from disasters which would have ruined other nations.”

In April, One Hundred Years of Remembering, Praying, Commemorating, and Demanding Justice for the wrongs committed by the perpetrators of the 1915 Genocide of the Armenians will be marked by an historic event in Armenia at Holy Etchmiadzin—the Canonization of our Martyrs. His Holiness Karekin II and His Holiness Aram I will preside together over this momentous ceremony.

As candles burn, choirs sing, and incense fill Armenian churches on our National Day of Remembrance, I will light three candles: One for our Martyrs, One for Armenia, and One for Armenians Everywhere.

“Dour ashkharhis khaghaghoutiun,

Azkis Hayots, ser, mioutiun.

Der voghormia, Der voghormia…”

“Bless the world with peace, and the Armenian Nation with love and unity.

Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy…”

—Gomidas Vartabed

***

References

Boyajian, Dickran H., The Pillars of the Armenian Church. Watertown, Mass.: Baikar Press, 1962.

Campbell, J. Alston, In The Shadow of the Crescent. London: Marshall Brothers, 1906.

Chicago Daily Tribune (now Chicago Tribune).

Chookaszian, Levon, Arshag Fetvadjian. Yerevan: 2011. (Painting of Narekatsi)

Hambartsumian, Vahan, Village World (Kiughashkharah), translated from the Armenian by Murad A. Meneshian. Providence, R.I.: Govdoon Youth of America, 2001.

Narekatsi, St. Grigor, Speaking with God from the Depths of the Heart, translated from the Armenian by Thomas J. Samuelian. Armenia: 2002. (Narekatsi quote)

Knapp, Grace H., “Grace H. Knapp Papers—All Correspondence, 1895-1916.” Mt. Holyoke College Archives & Special Collections. South Hadley, Mass.

Simeonian, Very Rev. Arsen, Gomidas Vartabed. Boston, Mass.: 1969. (Drawing of Gomidas)

The Alliance Weekly: A Journal of Christian Life and Missions (now ALife). Christian and Missionary Alliance, Colorado Springs, Colo. (Archives Department)

***

Note: The author wishes to express her deep appreciation to the following for kindly providing material used in this article:

Christian and Missionary Alliance Archives Department staff

Mt. Holyoke College Archives & Special Collections staff