Setting Apart the Change Makers from the Pretenders

Special for the Armenian Weekly

We are less than one month out from the all-important National Assembly elections in Armenia, and with nine political parties and blocs confirmed as participants, the battle lines have been drawn. However as we take a closer look, we realize that there is a missing ingredient that may critically flaw this election campaign and the future government it elects, and that is the lack of a battle of ideologies.

![]()

‘We are less than one month out from the all-important National Assembly elections in Armenia, and with nine political parties and blocs confirmed as participants, the battle lines have been drawn.’

In countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, and most of Europe, we are accustomed to an ideological battle between the “right” and the “left” that determines so many of the votes each election. For example, in the U.S., if you are conservative and stand for small government with more faith in business, you are inclined to vote Republican. While if you are progressive, believe in government-funded benefits for medical care and education, you are inclined to vote Democrat.

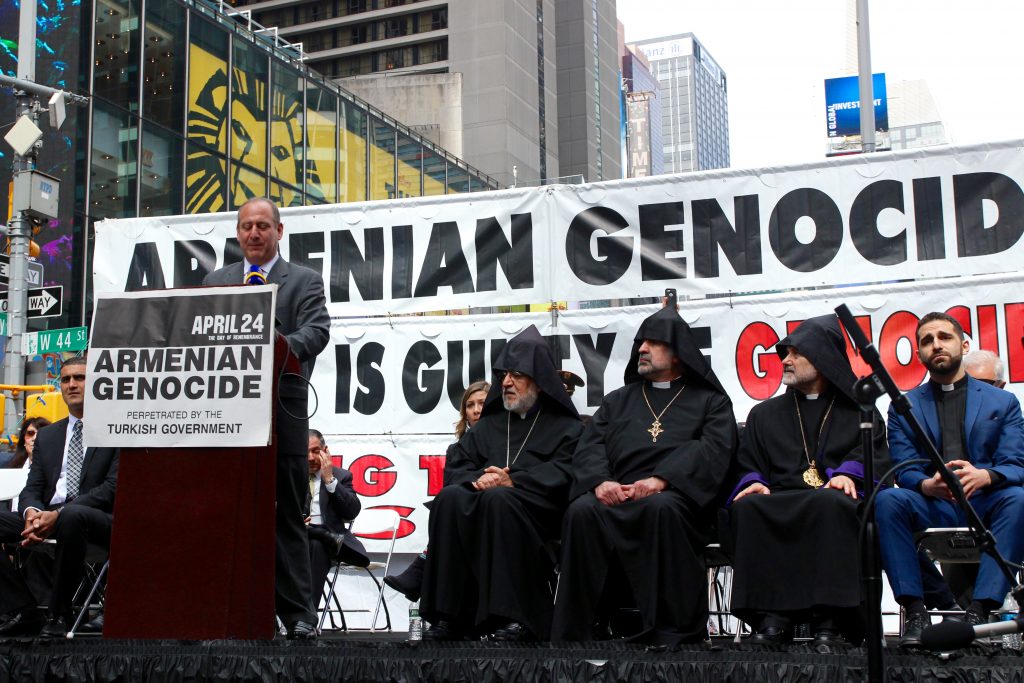

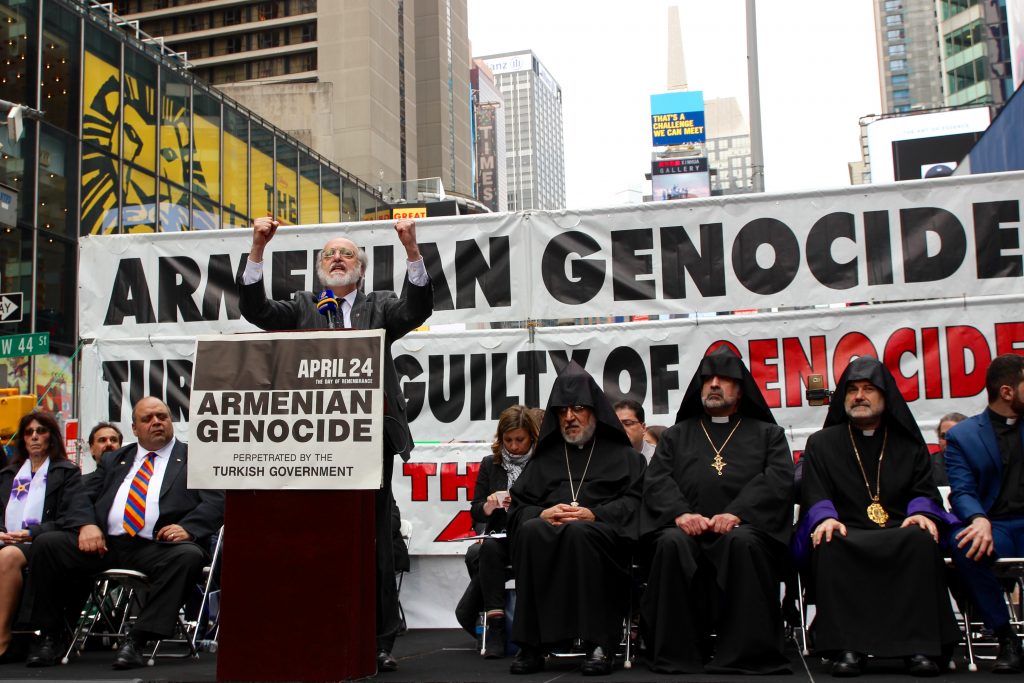

Naturally, key issues can swing your vote from your inclinations (e.g. many Republican Armenians voted for 2008 Democratic Presidential candidate, Barack Obama after his pledge to recognize the Armenian Genocide, while many progressive Canadian-Armenians were great supporters of the champion of Armenian Genocide recognition in that country, the Conservative Party’s Stephen Harper).

However, party ideologies ground political debates in these countries and bring sensibility to the positions of the participating political parties. A sensibility that clarifies what political parties and candidates actually stand for at their core. A sensibility that is tragically missing in Armenia’s political debate right now.

Conservative political parties try to “get out of the way of businesses” (their primary funders and voters) by taxing them less, while progressive political parties try to “deliver for the working class” (their primary funders and voters) with initiatives like higher minimum wages and free doctor visits through government-funded Medicare-like initiatives.

This is why, for example, right-wing conservatives do not typically offer free doctor visits as they cannot afford to pay for such promises with their income streams compromised by a commitment to reduce taxes on businesses. And left-wing progressives often promote taxing larger businesses more to care for the working class and the poor, and will typically propose initiatives like government-funded free doctor visits.

In Armenia, most of the players are ridiculously coloring themselves as both conservatives and progressives with their early policy platform announcements. This is because what has united them in their parties or their blocs is not a base political ideology, but rather a common enemy–the ruling Republican Party of Armenia (RPA).

This phenomenon—of parties and blocs lacking common and defined ideologies—is destined to lead to internal failings down the road. It could lead to a potentially divided party or bloc leading Armenia’s next government, as well as to potentially crippling divisions in the opposition. This phenomenon is, therefore, very dangerous for an Armenian Republic that is at a critical crossroads.

The ruling RPA and Gagik Tsarukyan’s bloc led by his Prosperous Armenia Party (PAP) are shaping as favorites—a favoritism that has been measured by their respective wealth of resources rather than by scientific polling.

The bloc formed by prominent former ministers Seyran Ohanyan, Raffi Hovhannisian, and Vartan Oskanian is being painted as a credible force by their supporters, while another bloc called Yelk (Way Out)—led by opposition Members of Parliament from the Enlightened Armenia, Civil Contract, and Republic parties—is also making noise.

Armenia’s first President Levon Ter-Petrosyan, ever-present in elections since the country’s independence 25 years ago, is also leading a bloc as head of his Armenian National Congress (ANC) party, while the Armenian Revolutionary Federation– (ARF)— currently in a cooperation arrangement with the ruling RPA—is entering the elections on its own, hoping to build on its current five-member team in Parliament (National Assembly).

The remaining political parties that are expected to struggle most to reach the 5% threshold to gain seats in the next parliament are the Armenian Revival Party, the Armenian Communist Party, and the Free Democrats.

In recent weeks, the participating parties and blocs have formed their candidate lists and have held conventions and press conferences where they have revealed their mottos and core visions, which have formed the basis of their policy programs that have been released now that official campaigning began on March 5.

Only a minority of the aforementioned nine players asking for Armenia’s vote are ideologically grounded, and this article will dig deeper into the top six players. The last three of the aforementioned are less likely to feature in the next parliament (although it must be noted that the Armenian Revival Party was once called Orinats Yerkir, and like the Republican Party and Tsarukyan’s Prosperous Armenia Party [who were all partners once upon a time], has been accused of buying votes and rigging elections in the past).

The ruling Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) is conservative, although their members say their ideology is “Njtehakan”, referencing a progressive Socialist hero of Armenia and a pioneering member of the ARF for much of his political life, Garegin Njteh.

![]()

An RPA campaign poster featuring Prime Minister Karen Karapetyan (Photo: RPA)

The fact is that the RPA’s record over the last 20 years in government has delivered little to the working people in terms of social welfare, while their major supporters are the wealthy and the maligned oligarchy, including current Prime Minister and multi-millionaire Karen Karapetyan.

Karapetyan, who has proven himself a more astute manager of Parliament than his party predecessors, is helping his party “seem” different ahead of these elections. But in terms of platform, the RPA is running as a typical incumbent of a war-time regime would, promising continued “security” for the country if returned to government.

However, in what will be more free and fair elections, this “more of the same” rhetoric from a very unpopular party will almost certainly see the RPA lose seats. But its hope is that the government’s more polished performance under Karapetyan—someone at least not expected to “short change” government finances as he is already a man of considerable wealth—has somewhat rejuvenated the RPA.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) (disclosure: my party of allegiance) is a Socialist political party with a 126-year history. As outwardly socialist, the ARF is clearly left of the political spectrum and therefore definitively progressive.

![]()

The ARF kicked-off its 2017 election campaign on March 5 in Yerevan (Photo: Photolure)

This is why it has been the only consistent driver of the Constitutional reforms (click here for more on the reforms), which is returning power to a collective voted for by 100% of the voting public, instead of a President voted for by (best-case scenario) 50% or 60% of the voting public.

The ARF leadership has released its election platform with progressive but “realistic” policies. Its leaders say their policies are more “realistic” than other progressive platforms, because the party’s current experience in government provides the ARF with insight into the real resources of the nation.

Further, the ARF election platform includes a strategy to break up the monopolies hijacking Armenia’s economy, which is programmed to be achieved through higher taxes, imposed on wealthy corporations that are using the country’s natural resources (e.g. mining), in order to level the playing field. This can also provide additional revenue for progressive policies to be paid for and therefore implemented.

Progressive policies the ARF has released as part of its program include furthering employment opportunities for Armenia’s youth post-military service to negate the emigration epidemic harming Armenia, ensuring the minimum wage and aged pension are raised to a fair level to ensure the ability for workers and the elderly to provide for their families, while government intervention is suggested in essential services (water, electricity) in order to provide greater social equality.

The nationalist ARF also has a clear position on Artsakh (Nagorno Karabagh). Highlighting its 126-year mantra of a Free, Independent and United Armenia, the ARF sees Artsakh’s future as a part of the Republic of Armenia. Therefore, it wants to maintain the Republic of Artsakh’s current independent status as a means of reaching that future goal. Therefore Baku’s recognition of the Republic of Artsakh must be a prerequisite for any negotiations and talk of mutual concessions with Azerbaijan.

The RPA and ARF are the only two contenders with defined ideologies, and as readers will determine from the above, they are actually opposing ideologies. This is one of the reasons why many in Armenia’s “free press” (those not outwardly owned by any party or bloc, but some with questionable motives) refer to the current government marriage of these two parties as a marriage of ideological contradictions. They justifiably question the ARF about the validity of such a partnership and receive answers through open, hard-hitting interviews with its leaders.

The ARF maintains that its partnership with the RPA was to lead the country onto a trajectory towards democratization (sighting the implementation of the constitutional reforms the ARF and RPA together promoted and achieved as a prime example), but points out that it remains a party on its own, and will run alone in these elections with a platform true to its ideological beliefs. Its leaders have communicated that the ARF will push their election policies regardless whether they end up in government or opposition, “as they have always done”. The RPA, to its end, is also running solo in these elections on its own record and platform.

While referring to the questioning of whether the ARF and RPA marriage is justifiable, this author’s expectation is that the same “free press” that questions the above contradiction of ideals will hold the below platform and partnership contradictions to the same standards during this election campaign. After all, the below are contradictory parties and blocs running as the alternate leaders of the Republic of Armenia at what is a critical juncture for the nation.

The Tsarukyan bloc is one of these contradictory examples. Gagik Tsarukyan is an oligarch, who is portraying himself as the man of the everyman because he uses some of his questionably-sourced earnings to make benevolent donations to civil society and organizations.

![]()

Gagik Tsarukyan is portraying himself as the man of the everyman. (Photo: PAP)

The 15-point program released by the Tsarukyan bloc states, among other things, that the bloc will increase the monthly minimum salary in Armenia to 80,000 AMD (around $165 USD) and offer three-year tax exemptions for the country’s small and medium businesses. The program also says the Tsarukyan bloc will reduce the costs of gas and electricity, while no student will miss out on a tertiary education for financial reasons, meaning this will be subsidized by a Tsarukyan bloc-led government.

These are obviously very progressive policies, meaning they come at a cost to an incoming government. According to projections, the promises are likely to cost at least 500 billion AMD. Note that the entire 2017 revenue of the current Armenian government is projected to be only 1.2 billion AMD, and this is a government already operating with a budget deficit and significant foreign debt threatening the country’s sovereignty.

Therefore, one would expect the Tsarukyan bloc has dedicated some of its 15-point program to addressing ways of increasing government revenue to pay for their generous promises. However, none of these 15 points suggests how revenue will be increased. If this reminds the reader of Greece before it was bankrupt, it is because it is exactly like Greece before it was bankrupt.

Let’s be honest; nobody really expected Tsarukyan to raise taxes on his fellow elite. Therefore, without increasing revenue, the only other option if these promises are to be accepted as genuine is reducing costs. Reducing costs at the volume required to meet the Tsaukyan bloc’s 500 billion AMD worth of promises will mean mass cuts to the public sector, which is the country’s largest employer.

This platform by the Tsarukyan bloc proves the importance of grounded ideologies in politics. Without grounding ideology, this program must be dismissed as populist and dangerous, likely to increase emigration due to job losses and threaten Armenia’s sovereignty by plunging it further into debt.

Interestingly, Tsarukyan is hardly interviewed by networks that are not his own and these contradictions are therefore not questioned on behalf of the voting public.

The Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanian bloc recently held its first Convention. A coalition made up of three individuals who have been ministers in governments that have been deemed corrupt at different stages of Armenia’s 25 years since independence is surely enough to raise many questions. But there are more questions that arise from the bloc’s lack of ideological continuity.

![]()

(L to R) Vartan Oskanian, Seyran Ohanyan, and Raffi Hovannisian (Photo: ORO Bloc)

For example, the person whose name sits in the middle of this bloc’s title—the socially progressive Raffi Hovhannisian—has been among the most vocal critics of governments that were served by his now-partners, Oskanian and Ohanyan (under conservative Presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serge Sarkisian, respectively). And why is Hovhannisian, whose first name as a former presidential candidate of note brings popularity to the title of this bloc, ranked at number 11 in their nationwide list of candidates?

This bloc also serves up Vartan Oskanian as one of its leaders, who is a modern chameleon of Armenian politics. He is so ideologically grounded that he has been a minister in a RPA government, then a member of Tsarukyan’s Prosperous Armenia Party, before forming his new “Hamakhemboom” (Unity) Party that forms part of this bloc. Yet the “free press” advocates at the network he founded verbatim cover his bloc’s Conventions and speeches, without so much as raising questions about what this man and his colorful bloc actually stand for.

In his appearance at the Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanian bloc Convention, Oskanian justified his request for Armenia’s vote by highlighting the “credibility” of the three amigos whose names form the title of his bloc. Is that really what Armenia needs? Three individuals replacing another individual, when this is election is about the start of moving away from individuals governing Armenia towards a collegiate government that is dominated by ideas?

And there is Seyran Ohanyan. Just months ago, he was the Defense Minister under the Sargsyan government which he is now opposing. He is an Artsakh war hero, which may offer him some leeway about a defection seemingly caused by a demotion, but he must at least be judged on what he is saying today when requesting Armenia’s vote.

Ohanyan spoke for 30 minutes at his bloc’s Convention, where he clearly articulated that he wants to increase military spending by billions of AMD and offer greater social equality through government intervention in breaking up monopolies. Just as clearly, he used his next breath to go on record to state that he will not achieve these promises by taxing the rich oligarchy in command of most of Armenia’s wealth through the very monopolies he proposes to break up.

Skepticism must be forgiven when a bloc led by a recent minister, standing to replace a regime that is beholden to oligarchs, outwardly declares he will not increase taxes on those oligarchs.

So how will Ohanyan and Co. achieve their promises? Oskanian hinted that he knows of funds that are available in the Diaspora, citing the example of $2 billion (USD) in the will of the late American-Armenian philanthropist Kirk Kerkorian.

Are we seriously hedging a country’s financial sustainability on a generous man’s one-off will and similar such examples Oskanian may or may not dig up? Are we seriously expecting to break up monopolies without increasing taxes on them and without upsetting oligarchs? These are among the many contradictions typical in a bloc only motivated to remove a common enemy, as opposed to a party or bloc grounded and uniting ideology designed to lead Armenia 2.0.

The Yelk (Way Out) bloc is made up of Members of Parliament of parties who have been consistent in their opposition of the current RPA regime, although not historically aligned in their methods. Their ticket is led by Edmon Marukyan of the Bright Armenia Party, the Republic Party’s Aram Sargsyan (brother of murdered former Prime Minister Vazken Sargsyan and a former Prime Minister himself), and Nikol Pashinyan of the Civil Contract Party.

![]()

(L to R) Edmon Marukyan, Aram Sargsyan, and Nikol Pashinyan of the Yelk bloc (Photo: Yelk)

We know that they have a pro-Western orientation through their joint declaration announcing their formal union, however this orientation mainly refers to foreign policy leanings, rather than internal policies that may govern an Armenia Yelk is proposing to lead. As we know, Western democracies like the U.S. are consistently critical of Russia (Donald Trump shaping as a possible exception) despite whether they are running progressive governments (e.g. Obama) or conservative governments (e.g. George W. Bush).

Therefore, a pro-Western bloc does not mean an ideologically grounded bloc. When asked to provide clearer definitions that led to the marriage of these three parties, Yelk bloc representatives have only stated that it is their strong agreement that the RPA, and particularly President Sarkisian, are their common enemies, and that Yelk is standing for election to replace him with a new generation of younger Armenian leaders.

They have not revealed anything new on the policy front in comparison to the above parties and blocs – more of the populist statements like those of Tsarukyan’s bloc covered above. And despite massive air time in the “free press,” they have only been able to consistently promote that they are a younger, fresher team that can be trusted to oust the RPA.

This explanation, while definitely popular and possibly noble, does not indicate any ideological grounding, therefore it should not attract confidence in voters about a future pro-Western and anti-Russian Armenia in Yelk’s control. Yelk, like its name suggests, is offering a “way out” from unpopular RPA leadership. However, it is not offering anything definitive beyond the “way out”, and this demands appropriate questioning on behalf of Armenian voters.

The bloc led by Levon Ter-Petrosyan includes his Armenian National Congress Party and the People’s Party of Armenia. (This author is unlikely to be very complimentary of anything led by Ter-Petrosyan, as evidenced by an article referring to him as a “virus” that needs political elimination.)

![]()

Armenia’s first President Levon Ter-Petrosyan (Photo: hraparak.am)

Ter-Petrosyan and his bloc argue that nothing domestic can and should be proposed for Armenia until the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabagh War. Therefore, he suggests resolving that war with his “peace now” mantra, which suggests giving up Artsakh’s liberated territories to Azerbaijan, then negotiating with dictator Ilham Aliyev—in good faith—to bring about some form of autonomy for the Armenians of that region one day in the future… maybe.

Essentially, this bloc is verbatim regurgitating from the handbook of Azerbaijan and pro-Azerbaijani negotiators, who are uninterested in the rights to self-determination for the Armenians of Artsakh.

As this stance is domestically unpopular, it seems clear that Ter-Petrosyan is trying to appeal to outside powers—like the U.S. and Russia—hoping one of their famous “interventions” in this election may lead to a “miracle” Ter-Petrosyan Prime Ministership.

In pre-campaign appearances, Ter-Petrosyan and his bloc allies have attributed most of Armenia’s problems to the Karabagh War; from the emigration epidemic to economic sustainability issues.

This means the bloc is actually suggesting to bring the country’s enemies closer to its borders, and then to open these same borders. This signals danger, even before addressing Ter-Petrosyan’s lack of ideology, which is typical of Soviet fossils who remain active in post-Soviet states.

Also noteworthy on Ter-Petrosyan is his most recent election loss as a party leader. His party only managed enough support for entry into parliament as opposition, when he decided that he cannot occupy one of those opposition seats because it would be “beneath him” as a former President.

Obviously, many questions must be asked to Ter-Petrosyan on behalf of voters, and one of those is whether a vote for Ter-Petrosyan’s bloc is actually a vote for Ter-Petrosyan, regardless of whether he wins or loses? If it is only a vote for Ter-Petrosyan if he wins, then the voter may choose to vote for any of the above alternatives, who are at least promising to stay the course to argue for their election platform regardless if their mandate is in government or in opposition.

This article exposes that ideology is missing from most of the players vying for Armenia’s vote in these elections. It raises questions that must be asked to address the missing pieces of each party and bloc’s puzzle in order to give voters a clear idea of what the next version of Armenia will look like under those contending to lead it.

We will continue to hope and pray for what is best.

To understand more about the rules that will govern and determine the April 2 Elections in Armenia, read “Elections in Armenia Explained”.